Lucite Embedments: What Works and What Doesn’t?

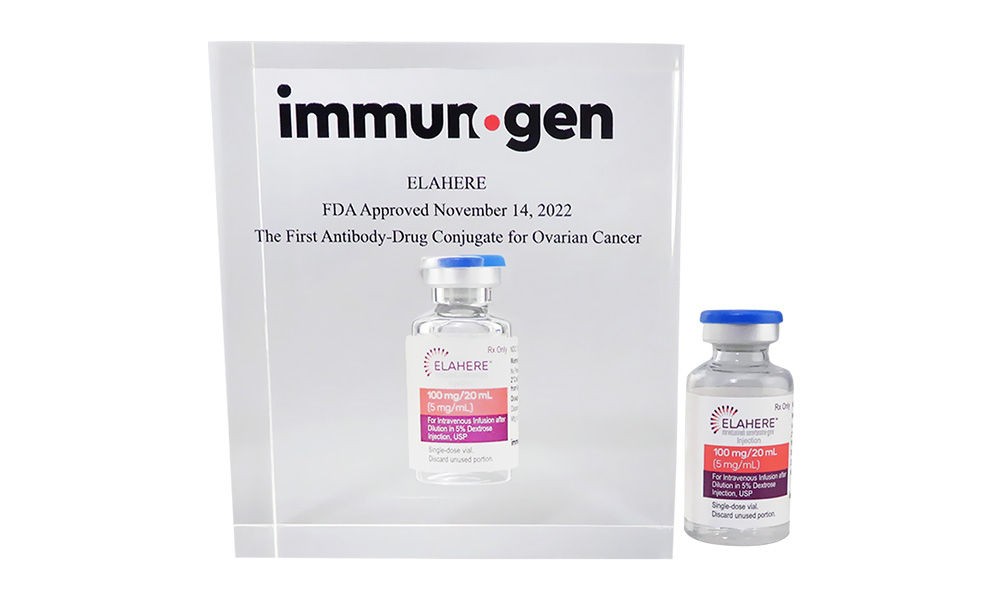

Lucite embedments can have extraordinary appeal and perceived value among recipients. The piece shown above is a great example.

It’s not hard to imagine how a commemorative recognizing the successful development and subsequent FDA approval of an ovarian cancer drug could have a visceral effect on recipients. Then factor in the added cachet for those whose dedication and expertise are being honored that the award actually incorporates that very drug.

And that effect holds not only for those recipients but anyone else who sees and handles that award.

That said, Lucite embedments can also be very tricky.

You need to know what will and won’t work, both practically and aesthetically.

There are any number of reasons you may want to place an object in Lucite. You may already have a very clear idea of what that object is.

Like the soldier who asked us to preserve shrapnel from the wound, he’d narrowly survived.

Or the client who asked us to embed a corroded bolt, the very one that supported—until it didn’t–a massive metal plate that then proceeded nearly to impale him.

Drug vial embedments—such as this example celebrating a clinical trial of a cancer treatment—can be tricky. Labels, for instance, can pose unanticipated challenges.

What Exactly is Lucite?

Most people consider terms like “plexiglass”, “acrylic”, and “Lucite” to be basically synonymous. That’s understandable. Though you may see these materails in your everyday like—in everthing from shatterproof windows to skylights to clear furniture—they’re not often identifed by name. Though these terms are used interchangeably, there are crucial differences between them.

Most of the confusion, by far, tends to focus on the differences between acylic and Lucite. Both are transparent, durable plastics.

Beyond that, Lucite is an acrylic—but a specific brand of acrylic first developed by DuPont. It is also a high-grade acrylic. So, simply put, while all Lucite is acrylic, not all acrylic is Lucite. As discussed below, the superior qualities of Lucite directly impact both the range and quality of acrylic embedments.

What Are You Planning to Embed?

More likely you’re (hopefully) not fresh off a near-death experience, and may not have quite that degree of clarity.

At this stage, you might simply be thinking of a Lucite embedment in conjunction with some sort of special event.

The occasion might be, for instance, a product launch or production milestone, a groundbreaking, or a regulatory clearance. Or you may simply need deal toys to commemorate a successful transaction.

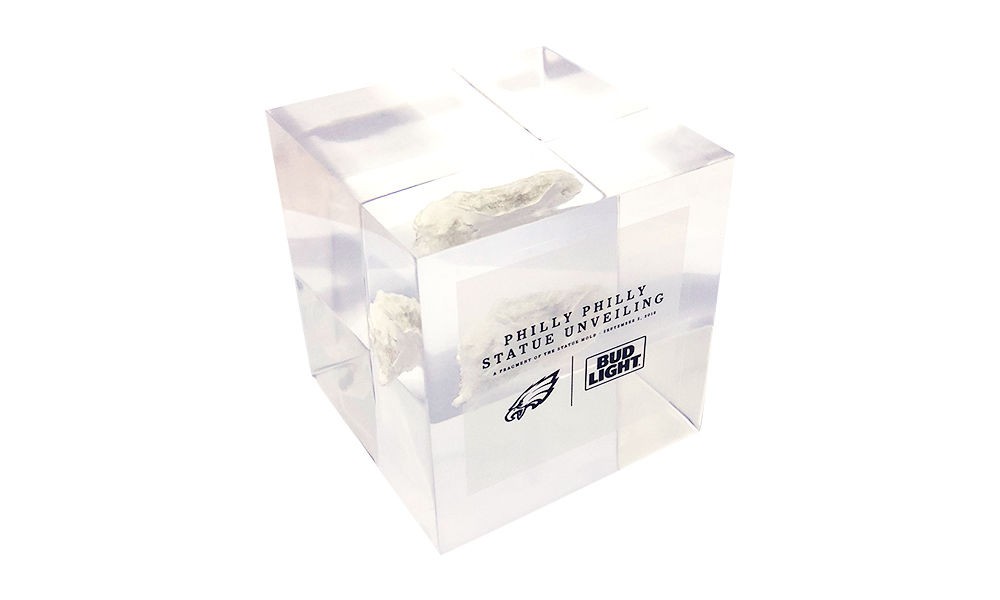

Custom Lucite celebrating the unveiling of the “Philly Philly” statue, commemorating a pivotal play by the victorious Philadelphia Eagles in Super Bowl LI. The piece incorporates fragments of the ceramic mold used by the sculptor.

Side view showing an embedment in Lucite of a row of test tubes.

You may just want to know what your options are. Can I put my (or my client’s) product in Lucite? Beyond that, what kinds of things can be put in Lucite (acrylic), and what should I know about the process going in?

This post will give you a short primer on Lucite embedments, and provide some tips on navigating the process with a minimum of time and effort.

This piece illustrates just how effectively Lucite embedments can showcase objects—even common, everyday objects such as these.

7 Tips for Successful Lucite Embedments

1) Be Aware That Certain Materials Just Won’t Embed

Embedding an object in acrylic involves a baking process. The object is subject to extremely high temperatures in an autoclave—similar to a kiln.

Some objects simply can’t withstand the intensity of the heat and will melt or singe. These include rubber, most plastics, painted objects, and certain kinds of paper.

An experienced acrylic company will usually be able to identify materials that will most likely pose a risk.

Sometimes it’s the very thing that signifies an object worth embedding that can make the embedment process dicey. The hologram on that prized Super Bowl ticket, for instance, is almost certain to fry during the baking process.

Again, a responsible vendor will be able to propose alternatives to embedment in a situation like this (such as a so-called “sandwich” piece to display your tickets).

If you’re not dealing with an irreplaceable or one-of-a-kind object, you’ll have the ability to test that object before proceeding with a full order. (See tip #6 for more on testing).

2) Recognize That Certain Materials Will Embed—But May Look Terrible

Yes, the piece shown below looks lousy.

But then again it’s supposed to look lousy. It’s the corroded bolt mentioned above—the one that nearly did in our client.

Aesthetics matter. And unless you’re also documenting a near-death experience like this, you’ll want to avoid embedding something that survives the embedment process, but just doesn’t work aesthetically.

A truly awful-looking Lucite embedment—though one that was actually intended to look lousy. But unless you’re also commemorating a near-death experience, you need to safeguard against bad aesthetics and lousy-looking embedments.

For example, clients are sometimes looking to embed a part or component that is routinely subject to high temperatures, and designed specifically to withstand them.

We once had a client looking to embed an aircraft engine part. The client (understandably) considered it a point of pride that the component could withstand extreme temperatures.

We conducted a test on one of the parts. The client was right: it did hold up to the autoclave baking.

But it looked terrible.

We ran another test, using another sample of the same part. It also came out poorly: discolored and tinged.

The outcome was hardly a reflection of the quality of the client’s product. The client’s product was an internal part of an engine, and its appearance was therefore not an issue; in fact, the piece was expected to show some discoloration with use.

But however high its quality, the product wasn’t suitable for embedment. The discoloration, though it had no bearing on the product’s performance, just didn’t look impressive—and therefore did not reflect favorably on our client.

And why would you want to embed a product that reflects poorly on you or your client?

The solution? We tested a different engine part. It worked. (Again, see tip #6 for more on testing).

3) Be Conscious of Inferior Materials in Lucite Embedments

The whole cachet of Lucite embedments springs from the fact they showcase–and, equally important, preserve–unique and sometimes irreplaceable items.

But if your vendor uses inferior materials, you can lose out on the “preserve” part of that equation.

Be aware that some manufacturers will substitute less expensive polyester plastic for the higher-grade cast acrylics that reputable vendors use.

These materials can (and usually do) yellow over a period of just a couple of years. They’re also more susceptible to scratching.

Again, your obvious goal in embedding an object is to showcase it for a long period of time. Manufacturers who skimp on materials defeat that very purpose.

4) Don’t Miss an Opportunity to Embed the Real Thing

Embedding an object is a way not only to display that object but also to highlight its unique character.

So it’s baffling when the opportunity to fully customize a piece isn’t taken (or, just as likely, not brought to a client’s attention to begin with).

Many vendors will simply embed generic materials—even when the genuine article could have been used.

For instance, they’ll embed the same oil in every Lucite embedment involving an oil drop. This may not seem like much of an issue. But what if you want to use “your” oil?

And what if, as in the piece below commemorating “first” oil, that’s the very purpose of the piece?

The client provided an oil for use in this Lucite embedment. Using the real thing, as opposed to generic oil, added to the cachet and perceived value of the piece.

In the same way, the purpose of the embedment shown below is to showcase the client’s high-grade oil, a sweet light crude. Many vendors will simply use for any embedment of this kind a vial of inky black “oil”—obviously completely inappropriate in this instance.

Instead of using the usual, generic black liquid so often used in oil drop embedments, the client here wanted to use its own—a very distinctive, light sweet crude. Using the client’s actual oil added considerable perceived value and cachet to this piece.

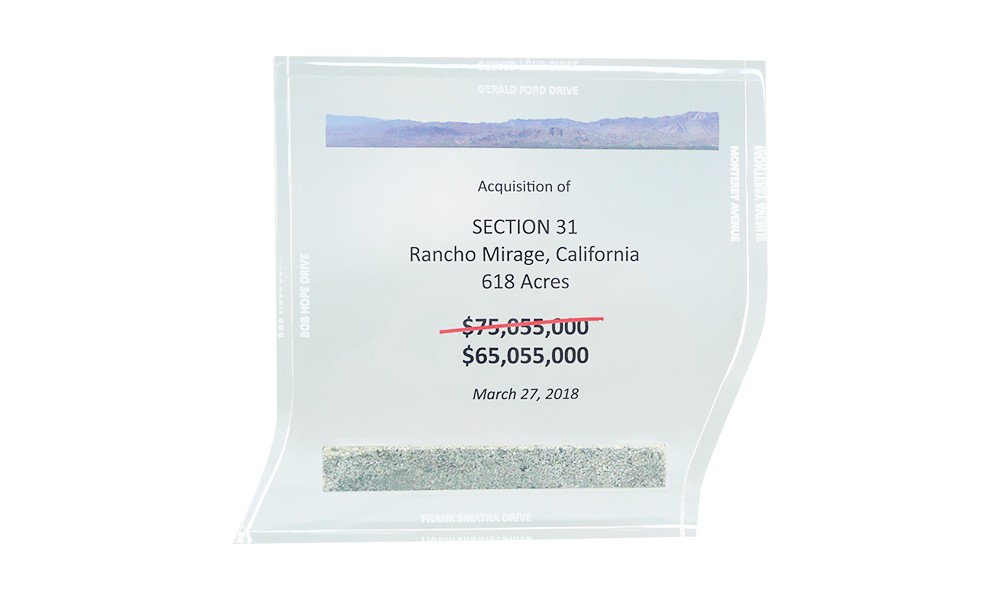

Similarly, the piece shown below incorporates sand taken from the site of a real estate deal. Just about any sand could have been used, but part of the cachet of this piece—what truly gives it its individual character—is that actual sand from the locale was used.

Custom Lucite commemorating a real estate transaction—and incorporating actual sand from the site, provided by the client.

Whenever possible, see if you can use actual materials.

5) Learn (Just a Little) Physics

The science of Lucite embedment isn’t exactly Nobel-worthy, but it’s somewhat interesting nonetheless.

As mentioned above, many objects will not withstand the extreme heat to which embedded objects are subjected. That much is fairly straightforward.

But the laws of Lucite physics can start to get weird and counter-intuitive due to something known as the “exothermic process”.

This phenomenon essentially involves objects having the capacity not only to withstand heat but emit it as well.

And certain objects will have the capacity to absorb and emit so much heat that it can cause the Lucite itself to break.

This can lead to some strange, and inconsistent outcomes. Some objects like peanuts, and (as shown below) a spice pod, will survive the embedment process. But rocks, by virtue of the radiating heat process described above, usually won’t.

How is it possible that a rock won’t survive the acrylic embedment process but this spice pod does? The science of Lucite embedment can sometimes be counter-intuitive and strange.

This custom Lucite—celebrating FDA approval of the obesity drug Plenity—offers another illustration of how idiosyncratic and unpredictable the embedment process can be. The champagne cork, as you can see, survived the baking process unscathed.

The technical aspect of all this most likely isn’t of much interest to you. But you should still be aware that there a couple of reasons—seemingly contradictory–why an object won’t successfully embed.

6) Be Willing to Test

Before proceeding with a full order, it is often necessary to test materials first to see if there are any embedment issues.

Test-embedding materials can be crucial.

This may seem like a needless, time-consuming step but it can ultimately save you a good deal of time, money, and grief. You need to recognize that, under certain circumstances, testing is a wise move, so try to be open to it.

7) Be Open to Considering Alternatives to Lucite Embedments

Your Super Bowl tickets with the hologram?

As noted above, you’re almost certain to ruin them by attempting an embedment. One solution is to use a so-called “sandwich” design, in which the ticket would be placed between two pieces of acrylic (not embedded).

Those of you who have seen older examples of this kind of sandwich “entrapment” may be wincing at this suggestion.

Chances are you may have seen some of the older-style sandwich pieces, in which the two acrylic pieces were held together with white plastic screws—which tended to look both tacky and ungainly.

More recently, most manufacturers have been using magnets instead of screws in sandwich pieces of this sort. The effect is much more subtle and streamlined.

There are also a number of creative ways to simulate embedment without actually subjecting the object(s) to the baking process. In the case of the sand piece shown above, the design workaround involved adding a compartment in the back of the piece (see below).

For more information on how you can make your Lucite embedments the best they can be, contact us and get started today.

Back view showing the design workaround in the real estate piece shown above. Since the sand couldn’t be embedded in the usual way, a recess was created to hold it.

Another example of an alternative to embedding: the Lucite “sand silo” in this deal toy used sand provided by the client.

Another example of design alternative to embedment of an object. In this case, the object is a robot.

A unique corporate gift, commemorating production in a mine in Sierra Leone, and incorporating actual iron ore concentrate taken from the site. Here again, the sand contained in the sphere is not embedded.

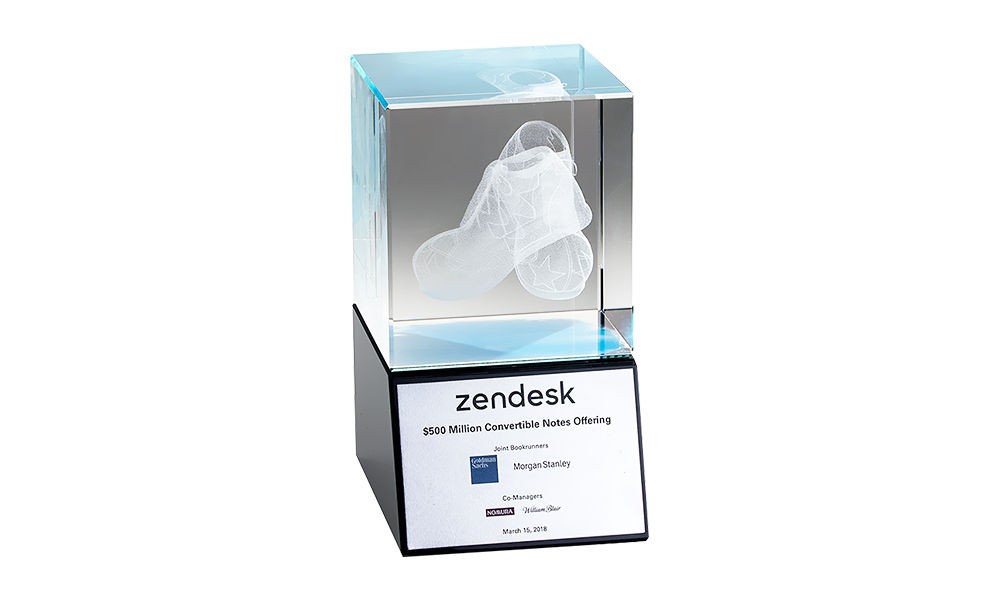

Finally, if you can’t find a way to embed an object but want to replicate it internally with a real 3-D feel, you may want to consider 3-D etching in crystal. An example of the technique also appears below.

An example of 3-D laser-etching technique inside crystal.

Another example of 3-D laser etching inside crystal.

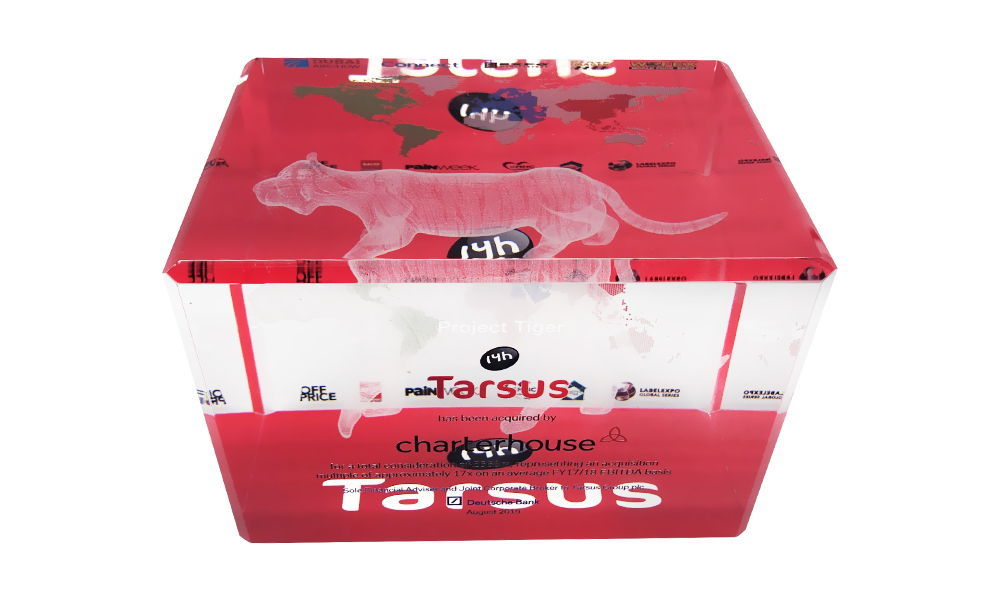

This top view provides an especially good perspective on this 3D-etched tiger.

A side view of the airplane featured in the crystal aerospace deal toy below provides an idea of the detail that can be captured in 3D-etching.

Unlike Lucite, objects cannot be physically placed inside crystal, but this technique should be kept in mind because the effect can really be stunning.

David Parry is the Director of Digital Strategy for Prestige Custom Awards, a designer and provider of custom corporate awards ranging from creative employee and client recognition awards to the NFL Commissioner’s Awards, and ESPN’s ESPY award. The company has almost 40 years of experience embedding objects in Lucite.